original: Gary Antonacci’s blog

Extended Backtest of Global Equities Momentum

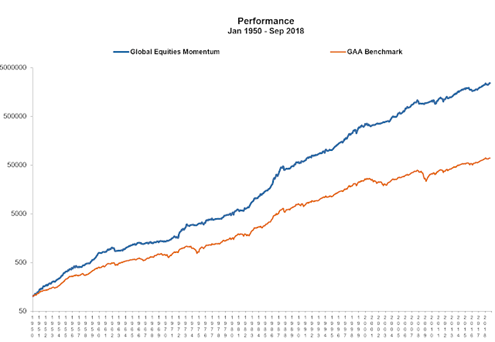

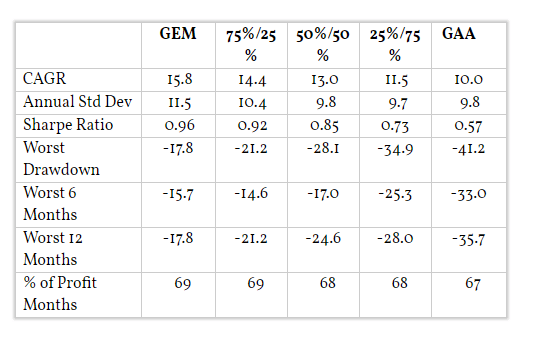

In 2013, I created my Global Equities Momentum (GEM) model. It holds U.S. or non-U.S. stock indices when stocks are strong and uses bonds as a safe harbor when stocks are weak.

When my book, Dual Momentum Investing, was published in 2014, I had Barclays bond index data back to 1973. Since one year of data is needed to initialize the GEM model, results went from 1974 through 2013. In 2015, I got access to Ibbotson Intermediate Government bond data. This allowed me to extend GEM back to 1970.

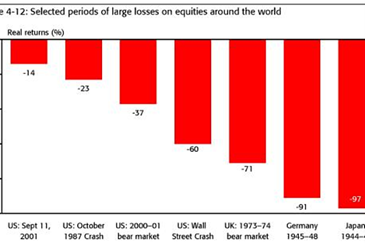

The extra bond data lets us see how GEM performed during the 1973-74 bear market. GEM was up 20% those two years, while the S&P 500 index was down over 40%. This was a short but impressive out-of-sample validation of my dual momentum approach.

Source: Dimson, Marsh & Staunton, Triumph of the Optimists:101 Years of Global Investment Returns, Princeton University Press, 2002

So, what is a good starting date for global investing? The first academic paper to point out the benefits of international investing was in 1968 [1]. There were similar papers in 1970 and 1974 [2]. The first mutual fund to make global investing available to U.S. investors was the Templeton Growth Fund that began in 1954. Asness, Israelov, and Liew (2017) in “International Diversification Works (Eventually)” begin their study in 1950 using GFD data. This seems to be a reasonable starting time. So GEM results will begin in January 1950.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

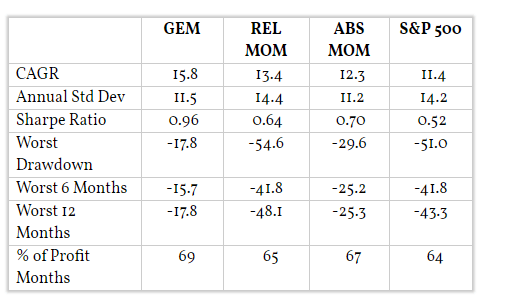

Relative versus Absolute Momentum

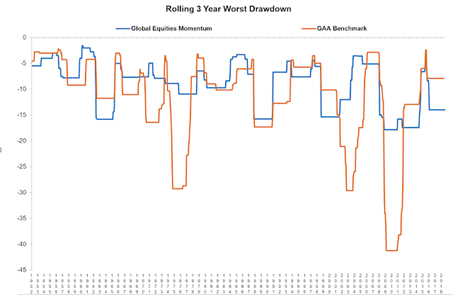

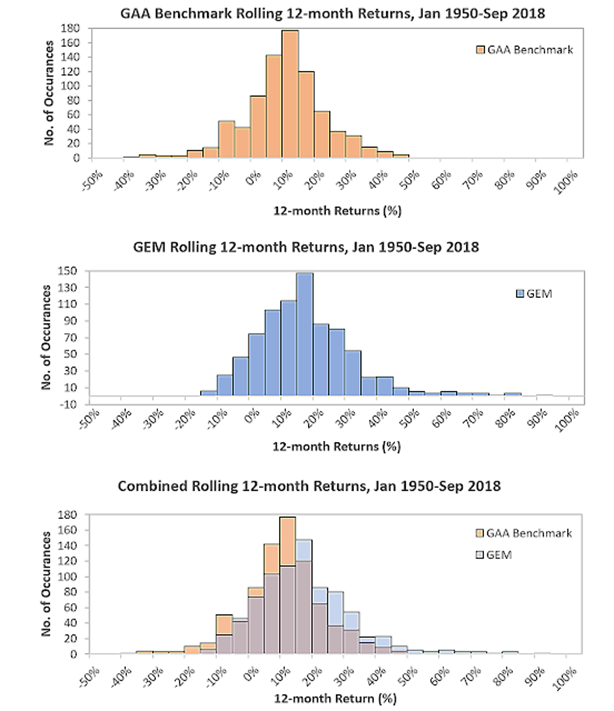

To better understand what is going on with GEM, I separated out its two components, relative and absolute momentum.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Relative momentum is where we switch between U.S. and non-U.S. stocks based on relative strength. Relative momentum still suffers from equity-like drawdowns. But for investors with a mandate to always be invested in equities, relative momentum gave 200 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

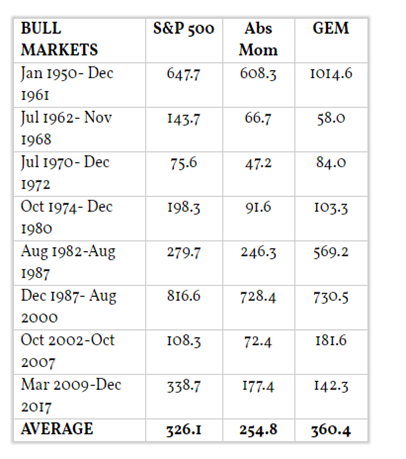

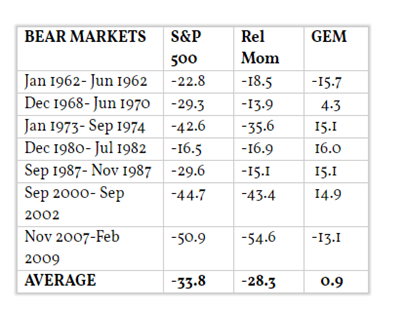

Absolute momentum gave less profit than the S&P 500 during bull markets. But dual momentum-based GEM produced more profit. Relative momentum by itself suffered nearly the same bear market losses as the S&P 500. But GEM, over the long run, eliminated those losses over this 68 year period.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

For more details about GEM or dual momentum, see my book.